I first encountered the city of Brasília while leafing through my grandparents’ books. Among the monotonous series of socialist towns listed and praised by an older Hungarian architectural edition, there was one that immediately impressed me. This was the Brazilian capital with its ambitious curves and UFO-like shapes as well as its incomprehensibly spacious public spaces. But the newly published Western author’s book also highlighted its uniqueness – none of these issues were sparing in their praise. According to some experts, Brasília is a model of a modern city, while its critics say it is a utopian dream that, despite its urban functions, cannot function as a real city. Is the Brazilian capital really such a town of contradictions?

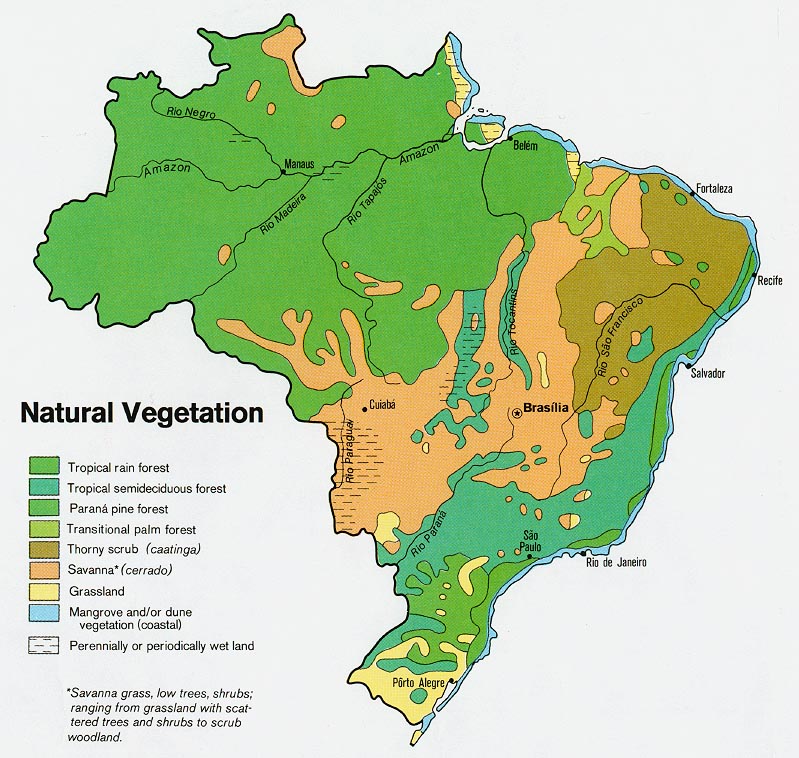

I land late in the evening. On the empty motorway, the taxi takes me to my accommodation without a hitch. 1,000-1,500 kilometres from the ocean, I’m in the Brazilian Highlands, or Planalto Brasileiro as it is known locally.

Location of Brasília /Source: CIA /

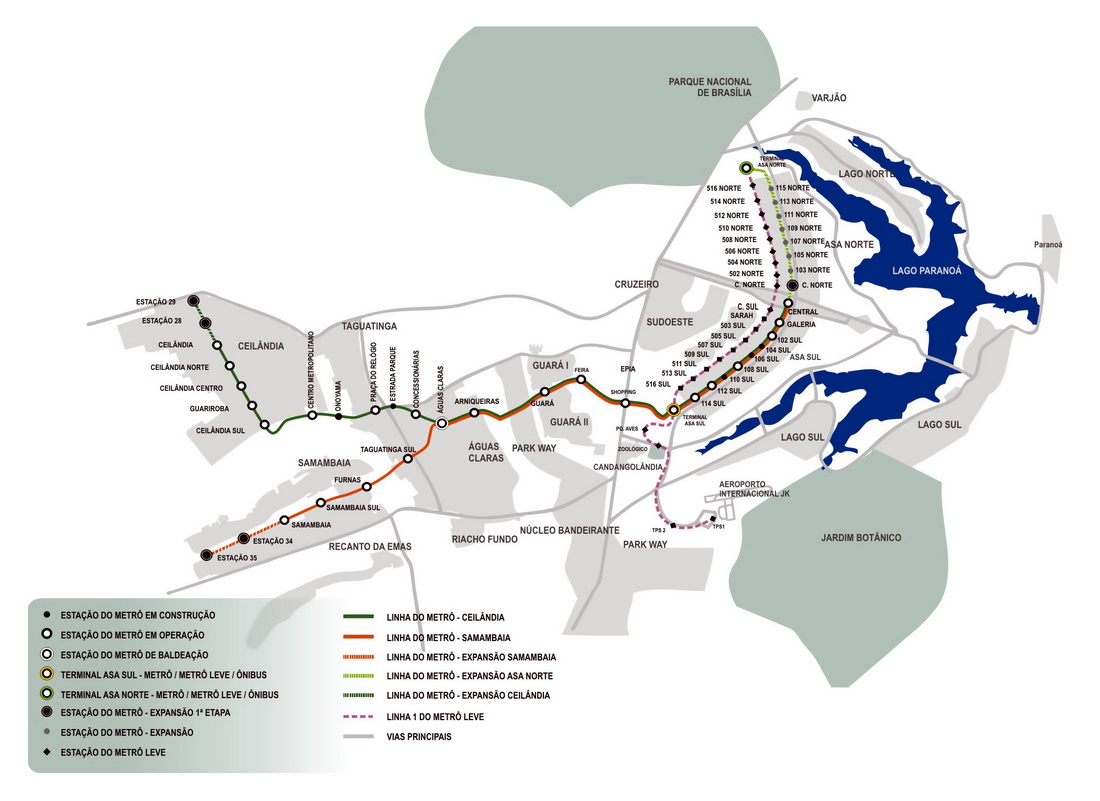

Here in the savannah-like Cerrado there is not a completely homogeneous metropolis, but interestingly a set of city blocks. These are separated by grassy wastelands and only the roads and subway lines shape them into one. I live in a district with new high-rise buildings, far from the compact city centre, which is why I’m not too happy about the metro workers’ strike.

The separate city blocks can be clearly seen on the map of the two-line metro network, inaugurated in 2001. /Source: internet /

An Alstom train arrives at Arniqueiras station near my flat. Only a very limited service is provided today, with a frequency of 15 minutes instead of the usual 5 minutes

What kind of men live here? Apart from some Middle-Eastern countries, this is the first time that I see a separate section or an entire underground coach dedicated for women, as advertised on the platforms.

After a difficult and then failed start of getting here from Salvador, I don’t want to take any risks now. As I may never have the chance to visit this rural interior part of Brazil again, I’m opting for predictability rather than the here seemingly impractical hitchhiking.

Within this country of the size of two European Union, travel is either by air or by couch, often overnight ones, and there is no passenger rail service. When I can, I choose the daytime buses, which not only allow me to see the ever-changing scenery, but also to get off in several cities for a day or two. So on my way downtown, I also drop by the bus station.

The endless variety of private bus companies. All I have to do now is to find the best value for money option for the route and time chosen

A giant poster of Brasília skyline at the bus station

Fortunately, the heat is not yet intense when I come up to the ground in the middle of the central business district, surrounded by high-rises. These are all headquarters of banks or large state-owned companies. At first I am surprised by the number and size of these buildings, but with a population of more than 210 million people, the country is on the scale of the United States or Russia. So that makes a difference.

The centre of Brasília is an average CBD, with a few office workers chilling in the shade of the iron and glass office blocks here and there. The rest either remain indoors or drive from their underground car parks to the shopping and entertainment district during their lunch break.

A Brazilian family on their visit to the capital.

Downtown, the locally known ipê-roxo trees are now taking the spotlight.

An election promise fulfilled

Latin American countries represent the periphery of the world economy, although their rich natural resources could have allowed them to achieve significantly higher economic development. This is partly due to the fact that their population and productive resources are distributed unevenly across their territories. The vast majority of Brazilians live in a relatively narrow coastal strip, while a large part of the country, covering half of the continent, is either uninhabited or sparsely populated.

The idea of opening up the interior dates back hundreds of years, and the construction of a new capital further from the coast was already ratified in the 1891 constitution. However, implementation only started around the 19th and 20th centuries, with the founding of a number of new towns (e.g. Goiânia, my next stop).

But it was not until the mid-20th century that the real attraction was to be revealed. That is, until 1956, when between two dictatorial periods a democratic leader was elected president. The determination of him, Juscelino Kubitschek, led to the birth of the symbol of an emerging, post-colonial Brazil.

The emblematic buildings and monuments of the city are the work of the brilliant Brazilian student of the Le Corbusier school, Oscar Niemeyer. For the town planning Lúcio Costa’s team was commissioned.

A bird? A bow? A flower opening its petals? Maybe an aeroplane? Brasília on the drafting board. At the time, the nearest paved road ended 600 kilometres away, but there were no railways or airports nearby either. /Image: Plano Piloto by Lúcio Costa. Source: Casa de Lúcio Costa/

And the inauguration a few years later – the designers and builders had less than 4 years to complete the first phase of the project! /Photo by the Hungarian born photographer, Thomaz Farkas/

Learning to read the city

I like old towns with their chaotically zig-zagging streets shaped by spontaneous evolution, where I can easily get lost if I put my map aside. Well, Brasília is not like that. In fact, at first glance, this high degree of orderliness seems to be more of a disadvantage: apart from a few monumental buildings, it is a monotonous mosaic of urban motorways and housing blocks.

The central city area is shaped like an aeroplane: the main east-west axis of the „fuselage” is the Eixo Monumental (Monumental Axis) and the north-south axis of the „wings” is the Eixo Rodoviario (literally the Highway Axis).

Plano Piloto /map source: internet/

These divide the city into zones with different functions: governmental, commercial, financial institutions, residential clusters, and cultural and religious buildings in between. In the absence of district names, locals orient themselves using codes similar to postal codes (e.g. SQN 403). Everything is invented and logical. But is it really liveable?

A Soviet new town somewhere on the Eastern European plain… or at least it seems to be. /Photo by Joana França/

But the residential neighbourhoods of the “airplane” are much more welcoming from ground level.

What are these? – step by step along the Monumental axis…

The city of Brasília was designed to truly represent a strong and rapidly developing country, the new superpower. Furthermore, unlike the colonial cities on the coast, the new capital, with its orderliness, is a true representation of the Brazilian flag’s motto “Ordem e Progresso” (“Order and Progress”).

A classic panorama of downtown Brasília – the junction of the Eixo Monumental and Eixo Rodoviario axes. Pedestrians are only rarely seen in the pictures, and this is not too much different in reality either. /Photo by Evaristo SA/AFP /

If I were in Albania right now, I would most probably be seeing a giant concrete bunker painted white in front of me – believe it or not, this hemisphere houses the National Museum.

I put my backpack in a locker and then, seeing the carpeted floor, I am happy to take off my shoes. After the thirty degrees outside, this is like a dream. And so is the interior, with its gentle curved lines.

Niemeyer revolutionised the design of Le Corbusier with arches, ramps and buttresses.

And the museum’s most unusual attraction is the batata plant.

I enter the central Brasília Cathedral through an entrance that descends into the ground. I walk below ground level when a huge hall unfolds with its yurt-shape roof.

The hyperbolic ferroconcrete elements open the building to the bright sky. St Peter and the angels.

Upon stepping out of the cathedral, I am greeted by the crew from Brasília TV. I can’t see foreign tourists on the streets, so I suspect I’ve become of immediate attraction to them. They are interested in my first impressions of the city and I am curious whether English could be the language of the interview. As they are apparently not excited by this language challenge – and I suppose they also don’t want to subtitle the programme – they dismiss even the idea of me speaking English. So may Spanish be our common tongue now… (But how I managed to speak almost fluently and intelligibly with my A0 level of Spanish, is still a mystery…)

If my growling stomach is not bad enough, here comes a cotton candy vendor

The National Library, the National Museum and the Cathedral

Now it’s really lunchtime!

The different functional zones mentioned above are separated surprisingly sharply. So much so that the residential belt is almost exclusively residential, the shopping area is a dense concentration of shops and restaurants, and the avenue of ministries is completely silent – there is only office work, and only during weekday working hours.

So now I have to get into the restaurant sector, possibly on foot. True, on the concrete heated by the scorching sun, this is quite a task, particularly given that spaces between buildings and functional zones are colossal.

I am not entirely sure that those who designed this city back in the late 1950s were thinking with the minds of its future inhabitants.

No much priority was given to walking and cycling. But where does this pavement lead?

Driveways that run under the buildings are the reason for the unfortunate need to descend below ground level. Then, after crossing the road, I have to climb the steps

The interior, reminiscent of an abandoned industrial site, is another example of the neglect that has become apparent in many places since the early years

Where there are no stairs to climb, one has to cross several hundred metres of these urban motorways. Riding an electric scooter or a bicycle would be another story, of course

But if you’re not too fussy and accept plastic tables and chairs, a simple snack bar or hamburger stand on the edge of a park will do. These small fast-food restaurants sprung spontaneously out of the planned city, and food trucks and ice-cream vendors with their rickshaw tricycles are also a sign that residents prefer not to drive between sectors at lunchtime, but to walk from their workplace to a nearby diner.

Installation of busy street food stalls – this was certainly not part of the master plans

But what’s the main issue?

Being a student of urban studies, the focus was obviously on urban and rural spaces as geographical entities. One of my professors drew a triangle to symbolize the components of a town or a village. At the apices of the triangle were the three fundamental components of them: the built environment, the economy, and the community. None of these can be missing from the formula. Well, any of them can, but then we can no longer speak of a town or a village, only of a settlement created for a specific purpose. In other words, impressive architectural design and ambitious urban planning principles are in vain if these spaces do not become inhabited and a (sense of) community does not evolve.

People simply need opportunities to meet and socialise, a mix of functions and, I think, a sort of orderly chaos too.

Of course, it is not necessarily good to blame the project for this. Since the basic need was simply to establish a governmental representation and administrative centre (settlement?) with the essential facilities for the apparatus and the effect of stimulating economic growth of the wider area. These goals were achieved. So successfully, indeed, that Brasília, originally planned for 500,000 inhabitants, is now home to nearly 3 million people.

Or I could quote Ricky Burdett, Professor of Urban Studies at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), who in a BBC interview, criticising the Brazilian capital, said that it might not be bad, but it is too early to judge. “Most of the places that we all adore, all of them, from Cairo to London, took either 5,000 or 6,000 years to get there, or 2,000 or 3,000 years to get there.”

“Let’s not be unkind. Let’s wait another 200 years and then talk about it.” – he concludes.

Further along the Eixo Monumental – a boulevard of ministries

Unlike Brazil’s former bustling capitals (Salvador, then Rio de Janeiro), Brasília is surprisingly calm, remarkably clean and public safety is noticeably better than I had experienced in previous days – something that is obviously well looked after here.

The capital is now the 4th most populous city in the country, although you wouldn’t guess it from the photos.

This is the avenue of the ministries, where there is nothing else around except government offices. And since there is nothing to do, you can see only a few pedestrians – but who would walk for several minutes through these barren urban wastelands in the sun…

President Kubitschek was determined to complete the great work during his term of office, so when the city was officially inaugurated, much of what is visible today was still unfinished. /This photo by Lucien Hervé, another Hungarian-born photographer, taken in 1961, reveal an even more deserted urban village./

Changing of the guards in front of the Ministry of Defence.

Palácio Itamaraty – the water world around the Ministry of Foreign Affairs building is certainly inspired by the Pantanal. And behind it…

Situated right at the “cockpit of the airplane”, is the National Congress building. Beneath the two domes (the paraboloid shape, which is open at the top, also hides a smaller dome) are the lower and upper houses of the two-chamber parliament.

I am keen to have a look at the whole building inside, but sadly there are no open tours today. However, these are free of charge and guided tours in English are also available by prior arrangement. The only requirement is that you dress smartly.

Waterfalls of the Palace of Justice

At first glance, the city’s important buildings may appear as brutalist structures, yet in their context they are all generous, airy, and even elegant.

A few words about the architect

Oscar Niemeyer (1907-2012) was the greatest modernist architect in Brazil and perhaps in Latin America, and the most influential after Le Corbusier in the 20th century.

Throughout his life, he supported communist ideals and his belief in the equality of society was a hallmark of his work. While he accepted that elegant buildings were property of the rich, he trusted that they could also bring joy and delight to ordinary people.

Although after the brief democratic era of the 1960s he went into exile to France, he remained in charge of many architectural projects in his home country. His most famous works are undoubtedly associated with Brasília, but many buildings throughout Brazil and even abroad have their curves attributed to him, e.g. the Serpentine Gallery in London, the headquarters of the French Communist Party, the Le Havre Cultural Centre…

Niemeyer never stopped designing even after his hundredth birthday /Photo: Valor Econômico/

“Fifty years of progress in five”

On 21 April 1960, three years after the completion of the master plan, President Juscelino Kubitschek arrived for the official inauguration ceremony. The great plan was achieved. His motto during his presidency, “Fifty years of progress in five years”, was met by his critics with the response “40 years of inflation in four years”, referring to the severe debt the nation-building process had driven Brazil into. The consequent budgetary crisis resulted in a sharp political shift: the military took power in a coup in 1964, after which the country returned to democratic rule only in 1985.

In addition to the financial problems, the project was subject to a series of other criticisms.

The environmental effects of the constructions as well as that of the “opening up” development programme for the interior are obviously tragic. The Planalto’s forested hinterland has been transformed over the years into an active agricultural region.

Furthermore, what was development for the Brazilian people, was accelerated degradation for the Xavante, the indigenous people of the area. Formerly enslaved, decimated by extermination and introduced diseases, they were also deprived of much of their native territory by land conversions and were relocated to reservations from the 1960s onwards.

In the urban planning studio an optimal living environment was designed for half a million people. Neither the urban planning nor the building design did segregate neighbourhoods solely by the future inhabitants’ income classes, which was in line with Niemeyer’s principles. But even though Brasília (the airplane-shape central urban block, plano piloto) was created to be home for both the poor and the rich, today it is exclusively home for the more affluent. Consequently, like other Brazilian cities, the whole urban agglomeration is now clearly divided according to income. The wealthy live in the plano piloto and in the green suburbs, while the poorer, who move to the city in search of better living conditions, settle in the sprawling peripheral residential areas or even in the shanty towns or favelas.

Despite the many contradictions, Brasília has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987 and was the first modern city to be nominated.

Further!

Seat next to the window, shady side, just as planned. Upon leaving the bus station, my bus is immediately on a motorway, but for another half an hour or more, the landscape is dominated by white residential blocks and housing areas. Then the landscape turns from a planned world into a wilderness of the green highland savannah.

Twenty years ago, flipping through the books, Brasília seemed like a place far beyond my reach. And, interestingly, that distance hasn’t completely disappeared even until now: its extreme uniqueness attracted and pulled me to come here, but now I have a kind of push feeling as well. And I think it is because of its excessive degree of organisation and its otherworldly dimensions.

Nevertheless, the experience overall was a very enjoyable one, and the iconic landmarks, with their brave and spectacular shapes, really blew me away!

After this powerful kick-off, the other planned cities of the Planalto or Highlands will have a hard time keeping me off my feet. We’ll see!

/Cover image: Cathedral of Brasília. Photo: terrainfinita.hu/

Be the first to comment